The Bittersweet Legacy

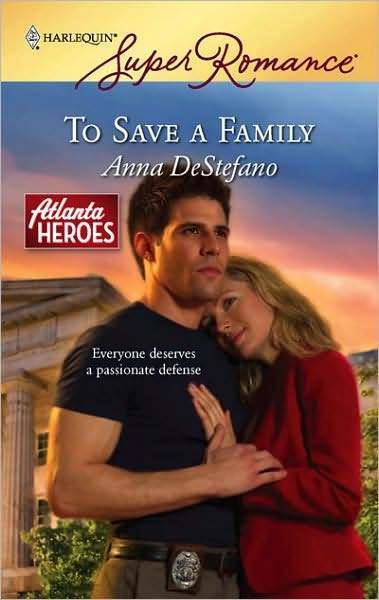

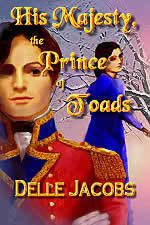

You can see I look like him. Same long face, long body. Even as I age, my face is taking on more and more of his features. There's a funny dent in my cheek exactly where he had one. And my hair, which was always stick straight, is beginning to curl like his.

You can see I look like him. Same long face, long body. Even as I age, my face is taking on more and more of his features. There's a funny dent in my cheek exactly where he had one. And my hair, which was always stick straight, is beginning to curl like his.We were alike in more ways than that.

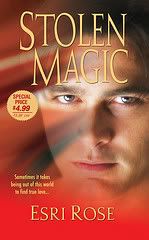

He was an intellectual who valued learning and wit, and a self-taught musician. He loved music, in fact, almost more than anything. In the photo, you see him in front of the electronic organ he has just built. He completed it four days before his 70th birthday. And then he sat down to learn to play it. I can still hear his high tenor voice, singing to his own playing.

He was an intellectual who valued learning and wit, and a self-taught musician. He loved music, in fact, almost more than anything. In the photo, you see him in front of the electronic organ he has just built. He completed it four days before his 70th birthday. And then he sat down to learn to play it. I can still hear his high tenor voice, singing to his own playing.Dad had me singing in front of the church congregation when I was 2 years old. I never knew what it was to be afraid of an audience because I had been there in front of them for as long as I could remember, and nothing scary had ever happened.

But he was a distant man, as far as his family was concerned. And he had a bit of a mean streak sometimes. I never understood that, and when he would belittle me, I felt it to the very bottom of my soul and believed myself unworthy of his love. I didn't know he couldn't do any better. It was what he had been given, by a father he despised.

He had a love of history. As we traveled, all five children and parents crammed into our 1954 Cadillac, he would often tell us stories of famous people. I didn't remember until recently how often he talked about Napoleon, but he was fascinated by the man who had come so close to ruling the world. And he had tales to tell about Huey Long, the Governor of Louisiana, for Dad had known him well and was nearby when that charismatic dictator of Louisiana had been assassinated. Dad despised those two dictators, yet he was obsessed with them. "Those who do not learn from the past are doomed to repeat it," he would often say.

I ate it up. I loved the history as much as the music. He questioned everything. He examined everything. Whenever he was not tending to his Gloxinias or orchids or Amarillis, he could be found drawing up some new idea for some kind of contraption or other, many of which he built. He'd say, "You never know if you don't try." And sometimes, "Let's run it up the flagpole and see if anybody salutes it."

He taught me to love plants and gardening, and to be fascinated with rocks. I just could never figure out Dad. It seemed even though I shared so many of his interests, he couldn't help but always tell me how I didn't measure up.

I remember:

I must have been about 6 when I came in from school crying because some bigger boys had been bullying and teasing me. Dad said, "If you don't want someone to get your goat, don't let them know where you tie it." I wanted comforting and didn't get it, but somehow that stuck with me. In later years, he said, "Don't give him the ammunition to shoot you." Which would have been better, the comforting or the axiom to guide me long after he was gone? It doesn't matter, because he could only give what he had to give.

I was 13 when we were traveling through the hot, dry land of Northern California on one of those horrendous family vacations, and suddenly Dad slammed on the brakes and pulled over. I thought it was yet another flat tire (we'd had three so far). But suddenly he was bending over, shouting at us to pick up the rocks. They were ugly, black things that looked like battered lumps of coal. But he was a geologist, and he had his rock hammer, and broke one open. Inside was a miracle of shiny, red and black striated natural glass. Mahogany obsidian. I've been fascinated by rocks and geology ever since. When we got home, my older brother and I learned how to chip arrowheads from the obsidian, and we took them to school and sold them for adollar apiece as "genuine Indian arrowheads". We were Choctaw, after all. Once I heard Dad bragging to a friend about it.

Yet when I told him once I wanted to be a geologist, he told me women didn't do that. He was right, of course. Women went to college to find husbands in those days. I could never grasp his idea that I wasn't meant for anything great. I believed everyone was, not just the boys. But in this way, he was a man of hs times. Women washed dishes and had children.

He taught me to experiment, to try the impossible, to sing and play music, to smash open rocks, to find out what makes the world tick, to look beyond a politician's smile and see what was really going on. I learned to design, to create. To write music, poetry, and stories. I learned to look into other people's souls, and to fiercely examine my own.

There were things I didn't learn, or learned because I didn't want to be like him. I learned to care about people, know and be with my children and give them support, in ways he could not have done. Because he was a brilliant but in some ways broken man. I know now that he loved me and my siblings. But I had to see through the cracks to find it.

The last thing he said to me before he died- I think he knew his time was coming- was that he knew he hadn't always been a very good father, and he'd done thngs he wished he hadn't. I wouldn't let him apologize, and I'm not sure why. I said, "Oh, Dad, we all do some things wrong. We can't help it. It's our job to do better than our parents, and maybe our kids will do better than we've done."

And so there was so much left unsaid when my brother called me the following week to say Dad had followed my advice and insisted on being seen by his doctor who kept telling him he "just had the flu". He had entered the hospital with congestive heart failure. He was told he needed yet another heart surgery, and he said, "No. I'm going home." He died before morning.

Yes, I am my father's daughter. My brothers tell me I am more like him than they are, but I think we are all like him in some ways. In spite of his limitations, he had a wonderful life. He was born in 1906, and would be 103 years old if he were still alive. He belonged to a different world from the one I live in now, and I don't know what he would have done if he ever saw a computer. Probably take it apart and figure it out.

He did a lot of things wrong, or no better than his own father. But he was a beautiful man.

6 Comments:

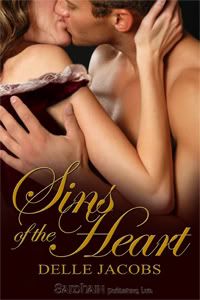

Delle,

What a beautiful tribute to your father. What strikes me most is that you saw both the good and bad in him. You're right in that he was shaped by a different world than the one in which we live. My favorite recollection you shared was of stopping for the mahoghany obsidian.

I think now, Mo, that a perfect world, a perfect childhood, perfect parents, would really be like Hell.

Part of my sadness for him is the joys he missed because he could only relate to those he loved in a sort of sideways way, and it takes an adult to comprehend that.

But part of my joy is that he gave so much anyway. That's part of my feeling now that I have had such a good life. Growing old has its own joys when you can begin to recognize the richness the nuances of the lives of those you love and how they fulfill the little niches and crannies in your own life.

But I know I wouldn't be a writer now if this one person had not shared his life with me. And being a writer gives me many lives to lead.

Delle, what an outstanding tribute to a man who was, above all, human. I see now where you get your insight into the human psyche. It's the imperfections in people that show who they really are, who they are trying to be and who they might be if they simply had more time. It's the trying to be that makes a difference. Some people just exist as they are and others try in ways only the most perceptive person can see. You saw that in your father.

Delle: your father and mine could have enjoyed many a lively debate. I can empathize with having a great teacher, but an emotionally distant father. To have closure, it is the greatest gift given. I'm glad you found it. I know I found mine.

And you know, it take a great heart to understand how his flaws were really a product of his times and how he really transcended his history to be the best dad he knew how to be...

Blessings!

Very nice story, Delle. You have a great attitude. He does sound like an interesting man. What happened to the electric organ he built? Very cool that he built one!

Delle,

The minute I saw his picture, I thought Delle! And I guessed right. I do know he raised a beautiful daughter--inside and out.

Post a Comment

<< Home

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]