USING STORY BOARDS AND FRIENDS TO HELP YOU PLOT

By

Debra HollandI wrote my first historical romance because a scene came to me as I was trying to take a nap--a couple riding along a river. Then I had to figure out what the story was. I wrote about ninety pages before I discovered RWA and my wonderful writing teacher, Lou Nelson and REALLY learned to write fiction. (Active verbs, who knew?)

Thanks to Lou, that book,

Wild Montana Sky, didn’t end up under my bed, but instead won a Golden Heart.

After I finished WMS, writer friends told to have a second book ready, so if an editor asked me for another book, I’d have one to offer. I started writing,

Starry Montana Sky, this time with more of an idea of the story.

Then I became sidetracked into writing Science Fiction and Fantasy. I tend to reread my favorite fantasy series about every other year. Five years ago, I’d just finished about my 10th round of Mercedes Lackey’s Companions/Valdemar books.

I was driving to work thinking about her work, and I said out loud, “I could never write like that!” Being a psychotherapist, I had to challenge myself on my negative attitude. I responded by saying “How do you know? You’ve never tried. Don’t say you can’t until you’ve given it a good try.”

So I took up my own challenge and started to think about a fantasy world. By the time I arrived at my office, I had the bare bones of

Twinborne Trilogy, Lywin’s Quest. I scribbled down my notes and mentioned the ideas at my next critique group. Everyone liked the story and encouraged me to explore it more. Two months later I described the story to my writer friend, Elda Minger. She also encouraged me to write the book.

For each book I write, I buy a small notebook with pockets. I carry the notebook with me and scribble down anything that pertains to the story. The need for pockets came from the times I didn’t have the notebook with me, and I’d jot notes on a napkin or the back of a business card. These got tucked into the pocket of the notebook.

For Twinborne Trilogy, I bought a notebook with three sections because I had wanted room for each book of the trilogy.

During the time I constructed

Lywin’s Quest, in my critique group, Lou embarked on lessons about plot structure. In every session, she lectured about a different part of the Three Act Structure.

As Lou lectured, I’d dutifully take notes, then a scene for LQ would hit me. I’d pull out my notebook, open it next to the paper I was using to take structure notes, and scribble the scene down.

Soon, I had a vague outline in my notebook, but it was incomplete. Because I was building such a complicated book, I wanted a more visual way of seeing my story, and I knew I’d need some help.

I consulted Elda, who had plenty of practice with plotting in groups. Using her suggestions, I invited three of my writer friends, including Elda, to a plotting retreat at my cabin in Big Bear Lake, California. We drove up for the weekend, and each of us planned to take half a day to share the plot of our story and get help from the others in fleshing it out.

We brought the following supplies to help us plot:

· One large cardboard backdrop. (If you think of a three-sided backdrop to a science project, you get the idea.)

· A stack of sticky notes/Post Its in various colors.

· Markers

· White poster paper

· A roll of tape

· Various baked goods, candy, and other snacks

On Friday night, we each took three sheets of large poster paper, one for each act. Then we filled out a sticky for every scene (that we knew of) in our books. On the sticky, we briefly wrote in big letters what took place in the scene.

We used different colors for the hero, heroine, and villain. We also used a second sticky, on which we’d mark various plot points (like DM for darkest moment) and place it next to the sticky that described what happened. We’d post blank stickies (in still another color) on any scenes where we didn’t know what was to happen.

Once we filled out all the stickies, we lined up the scenes on the paper, until all the scenes in the act could be seen, a colorful, giant chart. So although we didn’t have pictures of our scenes like are used in making movies, we had our own form of storyboards.

The next day, one of us taped her three charts to the cardboard backdrop and propped it on the end of the dining table. Then she explained each sticky in the story. Everyone could see her weak areas and empty spaces, and we’d brainstorm ideas to strengthen or add to the story.

As the writer changed or added to her plot, she moved stickies around and added new ones. We didn’t stop until we finished each writer’s whole book, but we managed to keep to our half a day per person deadline. It helped that the other writers had simpler stories that they intended to submit to one of the Harlequin/Silhouette lines.

At the end of the weekend, we had four tightly plotted books. Tired, but satisfied with our work, we rolled up our papers and took them home.

Over the next months and years (I veered back to writing the historical and another fantasy series,) when I wanted to work on LQ, I’d take out my charts to make sure I stayed true to what I’d plotted. I added a LOT more scenes to the book than I’d originally plotted, keeping track of my ever-expanding outline in my notebook. But the threads of the plot stayed fairly true to my chart.

I finally finished LQ. (At 125,000 words, it’s a BIG book.) Afterwards, I unrolled my tattered charts, spreading them across my bed. I stared at them for a long while, remembering. The storyboard process had given a structure to my dream of a story and made it real. And because of that realness, I could write and finish the book. What a wonderful feeling! (I’m not sure I’d have finished it if I hadn’t spent that weekend in Big Bear.)

Lywin’s Quest was the last fiction book I wrote. I’ve since turned my attention to nonfiction, although I’ve done some revising my other books. But I have new story ideas clamoring for my attention, and one of these days I’m going to head up to Big Bear with a group of writer friends. Want to come along?

Labels: plotting, writing

This week on the Wet Noodle Posse

We want to thank our monthly coordinator Theresa Ragan for keeping the conversation going during March. We switch to the topic of Conflict April 1st. And remember, we have one more day, March 31st for you, our readers, to win that $20 gift certificate from Borders. So make sure to respond to our blog tomorrow.

Monday, March 31st: Debra Holland "Storyboarding"

Tuesday, April 1st: Lorelle Marinello "Conflict Introduction"

Wednesday, April 2nd: Delle Jacobs "Let's Plotstorm a Conflict"

Thursday, April 3rd: Janet Mullany "Love = Conflict"

Friday, April 4th: Noodler New Releases!!!

The Wet Noodle Posse would like to congratulate readers CM and Doglady and noodlers Theresa Ragan and Priscilla Kissinger for finaling in RWA's Golden Heart Contest! We'd also like to congratulate noodler Stephanie Rowe for her RITA nomination!

Labels: writing conflict

Q&A Friday

It's time for Reader's Questions. What's a question you've always wanted to ask about plot? About anything related to writing? Noodlers are ready to answer.

Don't forget, posting puts you in the drawing for this month's prize--a $20 gift certificate from Borders, courtesy of monthly coordinator and 2008 Golden Heart finalist Theresa Ragan.

Labels: writing questions

Avoiding the Dreaded Info-Dump with guest blogger Kendra Leigh Castle

I’ll never forget the day I found out I had a problem. I’d just received my scores from the very first contest I’d ever entered, and sat eagerly parsing the comments for direction on my beloved WIP. It was the standard three chapter contest, and I knew, just knew, that I had a great opening. Even if chapter two had always seemed a little…bloated. Didn’t matter, right? Chapter two was necessarily chock full o’ crunchy goodness, and probably the judges would love it best of all. I mean, who wouldn’t love the entire tale of how my spunky heroine had come to own her romance-centric bookshop, complete with amusing flashback? Yeah, yeah, so the wounded werewolf hero was staggering toward her doorstep even as she did her detailed reminiscing. So what?

I will now summarize for you the general opinion of those three wonderful, insightful judges: “This is a great story. It’s probably going to sell. But you really need to do something about the glacial pace of chapter two. Do you really need to tell us quite so much?”

As I thought about it, the revelations came quickly: the 420-page failed manuscript living in a box in my closet, the fact that anyone with eyes and a pulse would be able to ace a complete biographical quiz on my heroine after her very first chapter…yeah, it all came together at that moment.

Hi, my name is Kendra, and I’m an info-dumper. Well, recovering info-dumper, if you want to be specific. Because even pantsers like me have a method to our madness, and I’ve learned to recognize certain signs that mean I’m doing my usual and stuffing too much backstory into one of my first three chapters. The things that tell me, “Uh, Kendra, you’re going to want to stop, go back about four pages, and start using the delete key now. Because unless I’m mistaken, no one will ever need to know the name of the dog your heroine had when she was four.” Among the warning signs:

1. I’ve gone more then two pages with almost no/no dialogue

2. Something cool is about to happen, and yet my character is thinking. And thinking. And thinking…

3. It’s early in the story, and I’m focusing on the past instead of moving the action forward in the present

4. All the pertinent parts of my character’s life story have emerged in the space of one or two chapters

I know I’m not alone. As writers, we love our characters, and we love their stories. Their whole stories, from start to finish, all of what made them who our hero or heroine is going to fall madly in love with. The difficult part, for me at least, was realizing that quite a bit of that backstory is only pertinent or interesting for me. It adds nothing to the book itself, and slows the pace rather than spicing things up. It was a hard lesson, leading me to educate myself (with no small amount of agony) in the art of “killing my darlings.” I must have cut five pages of fat out of that much-maligned chapter. Surprisingly, though, once I did, I found I had a tighter chapter with a snappy pace, and that there was even a cathartic aspect to editing down my own work. The amusing flashback and lengthy rumination on the past? Gone, baby, gone. And no one, save me, would ever miss them, which was most telling of all.

That said, and in the interest of helping other closet info-dumpers like myself (oh, the secret shame!), I have a few tips that have helped me write the kind of story I want to read, instead of the kind of story wherein I suddenly hit a wall of words and start skimming to get back to the action. Everyone has their own process, of course, but I’ve found that these things help me:

1. Write that backstory before you even start. Probably a good idea anyway, but like I said, I’m a pantser and am often guilty of, um, bad planning behavior. Write the whole thing, everything you want to know and can come up with about your characters. You want to talk about your hero breaking his wrist when he was twelve? Go for it. But do it in a separate file, or in a notebook, not right in your story. And if you suddenly think of some new twist to that character after you’ve begun writing in earnest? Avoid the temptation to wedge it into your current chapter and add it to that original file to use later. Let it settle. It may fit in better somewhere else.

2. Take a good hard look at what you do and don’t need in that voluminous backstory. What will reveal character and motivation? And what, though you might love it, is just extra? Make a list. Cross stuff out. Yes, it might hurt. Do it anyway.

3. Make a solemn promise to yourself to dole out the backstory in small amounts, no matter how great the urge to do otherwise (some small voice inside of me still screams, “No! They have to get to know him/her NOW!”).

4. Formulate a plan of action, and stick to it. This is a rub for pantser like me, who is sloppy about whatever sort of list I might make, but I haven’t found a better way around it. Divvy the backstory up into layers: what needs to be known up front, what can be revealed later, and best, things that can be hinted at and then revealed for maximum impact at a later time. This part can include paper and a marker, which makes me happy. I mentioned I’m messy, right?

Writing a chapter, or even a whole manuscript (like the one in my closet) that needs to go on a diet is no big deal if you’re willing to accept that diagnosis, then come up with strategies for circumventing counterproductive impulses and avoiding those dreaded pockets of info-dump. It’s amazing what we writers can do with willpower and the digital hatchet of the delete key. As for me, I’m eternally grateful to those three anonymous judges for both their encouragement and their criticism. I took their advice and trimmed my backstory, much as I loved what I had to lose. The end result? First a wonderful agent, and not long after, a book deal for me and the romance-loving heroine who thinks she’s helping a wounded dog and ends up with…well, quite a bit more than she bargained for.

Call of the Highland Moon

Call of the Highland Moon comes out May 1st from Sourcebooks Casablanca, and if you like sexy Scottish werewolves and sharp, funny heroines, I hope you’ll take a peek.

Thanks for having me as a member of the Posse for today, I love it here. Now go forth and whip those backstories into shape! Happy writing!

Kendra

www.kendraleighcastle.com Kendra also blogs twice a week at Sourcebooks Author Blog at:

www.wickedlyromantic.blogspot.comLabels: plotting, writing

Plotting With Theme - Esri Rose

Adding a theme to your novels can make readers relate to characters on a deeper level and give a mythic quality to your stories, making them more memorable and satisfying.

I’m going to give two examples of theme in movies most of us have seen: Bridget Jones’ Diary, and About a Boy. Both these films do us the favor of actually stating the theme.

Bridget Jones’ Diary

The theme here is, “Look for a love that doesn’t ask you to change.” Remember Mark Darcy saying, “I like you, just as you are.” That’s enough to give most women goosebumps. This theme resonated with women so much, it propelled both the book and the movie into superstardom.

Bridget Jones’ Diary presses home the theme by having the heroine ignore it for most of the movie. The framework of the movie -- all those notes about cigarettes, weight and alcohol units – are there to show that Bridget believes she’s unlovable as she is. She spends all her time trying to bend herself out of shape at work, at parties, and in the bedroom, instead of looking for people and situations where her unique gifts will work.

About a Boy

Here’s a movie that puts its theme front and center. In a voice-over right at the beginning, Will says, “No man is an island,” but he believes that he’s proving that theme wrong. Will spends most of the movie trying to convince himself that he’s happy with his island life. But he would have to live in a vacuum to actually be an island, and the human race comes knocking at his door in the form of Marcus. Marcus, although a kid, is more evolved than Will in that he realizes relationships are what make life worth living (especially for his mom, who is suicidal), and he provides the perfect foil for Will. In this film, there’s a point-counterpoint between Will, who struggles to remain emotionally disconnected, and Marcus, who struggles to connect despite the fact that his social skills are rudimentary.

Developing Your Theme

It’s difficult to decide on a theme right from the get-go, although literary writers do it all the time. Sometimes that’s all they start with. For commercial writers, it’s easier to write your first draft and then see what elements can be developed into a theme. One good thing about theme – if you make it really recognizable, it can infuse life into the quietest of scenes -- good news for romance writers who don't deal in bombs or evil uncles. In About a Boy, Will takes a bath, plays pool, and shops for CDs. These scenes would be snoozers except that they show how empty his life is. The theme allows us to understand both the character and the life lesson the movie is getting across. In fact, let’s just substitute life lesson for theme, and suddenly it all makes a lot of sense, doesn’t it?

How To

Think about how the conflict illustrates a life lesson your primary character hasn’t learned, and show how avoiding the lesson negatively affects your character's life. Make your secondary characters exemplify the lesson, as positive or negative examples. Construct situations that bring up the life lesson. Do all this, and you’ll impart a cohesiveness to your book that will make it very satisfying to read. It’ll have a theme.

Continuing Themes

A certain theme often appears over and over in a writer's books, and attracts an audience who loves to read books with that theme. A good example of this is Anne Tyler, author of The Accidental Tourist. Tyler’s characters are forever trying to escape their lives, their spouses, and their pasts. Her theme is probably, “You can't escape yourself.”

I’m working on the second in my Elves Among Us series (Bound to Love Her out in early May!), and if I have an overarching theme, it might be, “Don't live with fear.” Feel free to let me know if you think that's it.

A Pantser Dilemma--Plotting

To plot or not to plot. That is the question. At least that was my question for years. When I first started writing with publication in mind, I had a story idea, a couple of characters and an opening scene. I took those things and began a book. A year later I had a completed manuscript. I sent if off to a publisher, and five months later I received a rejection letter. That was the first of many rejection letters that I received over the course of twenty years of writing before I finally made my first sale.

During those years, I learned a lot about writing. I discovered that people had actually written books to tell other people how to write books. Amazing! I bought some and read them with enthusiasm, because these were going to be the key to publication. Sadly, that was not the case. I bought a few more books about writing and read, if not all, at least part of all of them. I discovered Romance Writers of America and a local chapter, Georgia Romance Writers. I joined these groups and found fellow writers who taught workshops and gave wonderful advice about writing. I joined a critique group, attended conferences and entered contests. I learned about self-editing, pacing, point of view, characterization, emotions, conflict, character goals and motivations, synopsis writing, and yes, even plotting. Even though I applied the lessons I had learned to my writing, I still didn't sell.

I began to suspect that I didn't sell, even after the lessons on plotting, because I still didn't plot my books before I wrote them. So I bought more books--books on plotting. Pictured below are just a few of them. These are all very good books, and if you are a plotter, they will give you lots of good information.

When I went to workshops on plotting, I did learn about turning points, the black moment and the final resolution. All of this was good, but I would find my mind glazing over with a thick haze when the presenters did graphs and charts with lines and boxes that you had to fill in with plot points. When I tried to plot the book before I wrote it, I would find myself working for hours without much to show for that time. I finally decided to push aside all the plotting charts and graphs when I couldn't answer the questions they required. I couldn't think that far ahead in my story no matter how hard I tried. I just started writing the book. What a freeing experience!

I finally realized that it is all right not to be a plotter. To me, writing a book is kind of like walking down a long corridor and opening the doors to rooms along the way to see what is happening inside. Each room represents a scene. I don't know what will happen until I get there and open the door. I might have a hint as I get closer and see the label on the door.

After I made the liberating decision to go with my gut and write by the seat of my pants, the next book I wrote won the Golden Heart for best inspirational romance in 2003, and the book I wrote after that was my first sale. My second sale was made on a complete manuscript. So I wrote the synopsis for each of those books after I had completed the book. According to my contract, I could make my third sale with a proposal rather than a complete manuscript. This meant I had to come up with a plot. Was I back to the terrifying prospect of plotting? Maybe. I had to come up with enough of an idea to satisfy an editor. This was uncharted territory for me. So I decided that I couldn't give a lot of details about the plot, but I could come up with the main characters' back stories, their goals, motivations and conflict that all stem from that back story. I would throw in a couple of turning points and the black moment that would hopefully be there when I actually completed the book. Now I have sold five books with either a proposal or only a synopsis. On each one, I have had to change the synopsis to fit the final story, because the storyline always becomes more clear as I write it. Nothing about my synopsis is written in stone. Such is the dilemma of the pantser.

So here is my final advice. If you are a pantser, don't let anyone make you feel inferior because you don't plot. If you are a plotter, have a great time making all your charts, grafts and outlines. For the panster, charts and graphs on plotting may come in handy after you have written the book to see whether you have all of those important plot points. But whatever you do, write the way that works best for you. Happy writing!

Merrillee

WRITING BEGINNINGS

By Norah WilsonWhen I signed up to write a blog about beginnings in the context of plot, I was thinking about story structure – beginning, middle and end. The beginning is probably the toughest part of a novel to write, because so much is riding on it. It will take up prob

ably 20-25% of your story, yet it has to establish tone and setting, introduce the main characters, and introduce the major dramatic question (story set up/situation). In those pages, you have to build a world the reader can believe in, peopled with characters whose actions are well motivated and make sense in the context of their own world views.

If that isn’t pressure enough, you have to do worry about your story’s literal beginning, the first line, first paragraph, page, chapter. The fact is, all that wonderful work you’ve done—the lovely character arc(s) you’ve designed, the intricate weaving of plot and subplots, the fabulous scenes you have in mind—will be all for naught if you don’t hook the reader early and draw them in to your story. I know, I know. Scary!

So how do you begin a novel in a way that will hook the reader and draw her in? That’s a darned good question, and one I struggle to answer every time I start a book. You can have the world’s most exciting inciting incident, but if the reader hasn’t bonded with your characters, they may just shrug and say, “Why should I care?”.

Let’s talk a moment about inciting incident. That’s the thing that happens to your protagonist to radically upset the balance of his or her life. It is the event that starts your story rolling and raises the major story question. To paraphrase Robert McKee, it arouses a desire in the protagonist to put things right, causing him to conceive his object of desire, his goal, the thing that will put things back into balance. For those of you who subscribe to the hero’s journey as your plotting companion, this is the Call to Adventure. The hero can resist the call initially, but eventually will answer it, launching an active pursuit of his goal (the quest).

Some authors hit the ground running with an explosive opening, plunging us

right into the inciting incident. That can certainly work; heck, I've done it. But for the most part, I prefer to try to establish empathy for my characters first. For hero’s journey fans, this would equate to showing your hero in the Ordinary World, before he gets the Call to Adventure. But don’t linger in the ordinary world too long! Today’s readers are primed for a fast start. As McKee puts it, “Bring in the inciting incident as soon as possible but not before the moment is ripe.”

Okay, back to making the reader identify/empathize with your characters so that they’ll give a hoot. For me, one of the keys is authenticity. You have to make that character feel real. You have to research the milieu until you can make me believe your police detective is the real deal, slouched at his desk in the detective’s bullpen, re-reading his report. Make me feel the knot in his gut, which he blames on the rotgut coffee, not the victim interview he just did. When I’ve really started to feel for this guy, who no doubt just wants to get home after an extended shift, hit him with that inciting incident.

If you’ve judged contest entries, you probably know quite a few things NOT to do in your beginning. For instance, do not try to jam too much information into the first few paragraphs or pages. I want to be oriented in a setting fairly quickly, but I don’t want to be inundated with so much detail that the pace drags. I want to get to know the characters, but I don’t want to have their backstory dumped on me all at once. I want to form a picture of the H&h, but not necessarily through long passages of detailed physical description.

Another key to great beginnings, I think, is to write loose and easy. Confident. That will show in the first paragraphs, and the reader will immediately relax, believing they are in capable hands.

“But I’m NOT confident!” you wail. Fair enough. But here’s another tip: You know that expression, “Fake it until you can make it?” Well it works in fiction, too. Once you’ve mastered basic craft, you just have to remind yourself no one knows you’re terrified. Relax, take a deep breath, and start writing as though you believe your reader will follow. That’s what I do! In fact, you be the judge. Here’s the opening of my current WIP.

This is not the inciting incident. It contains minimal setting information, and has no physical description of the characters. But does it work to draw you in? I’m not really going for empathy here (that comes later when we learn why he’s doing what he’s doing), but I’m starting to paint one dimension of my hero. Would you read further to learn who these people are and what’s happening?

Aiden Affleck hummed to himself as he lifted the brass doorknocker to summon St. Cloud Police Chief Weldon Michaels to the front door of his Carrington Place residence. Rapping twice, he stepped back.

What

was that tune running through his head? It had been with him since he’d risen this evening.

Audioslave? Nope.

Queens of the Stone Age? Un-uh.

Collective Soul? Yeah. Yeah, that was it. Definitely. He cricked his neck one way, then the other and felt the satisfying crack.

Ooh, I’m feeling better now.

The curtain in the bay window twitched, but Aiden feigned obliviousness. From inside, he clearly heard Michaels jam a clip into an automatic weapon. Aiden rolled his eyes. Nobody trusted anyone anymore.

“Who are you and what do you want?”

The voice came through the door. A cautious man indeed.

“I’m a friend of your wife’s,” Aiden called. “Well, more a friend of a friend, actually, but I have a personal message for you, from her.”

“Nice try. Now move on, before I call the cops.”

Aiden thought about knocking the door in. It was solid oak with a good deadbolt on it, but it could be made from cardboard and paperclips for all the challenge it would present. On the other hand, there was no reason to get messy.

He cleared his throat, did his best to summon a puzzled tone. “Well, hell, I thought you were the cops. Do I have the wrong address? I’m looking for Chief Weldon Michaels. Got a message for him from his wife Lucy. Pretty woman, ‘bout an inch over five feet, brown hair and eyes? Oh, and a real cute little daughter. What’s her name? Devon? Any of this sounding familiar?”

Silence for a few heartbeats. “What kind of message?”

“She wants to come home, but before she can see her way clear to doing that, we need to have ourselves a talk.”

Another pause, then the sound of the deadbolt retracting. The door cracked open, and Weldon Michaels peered out past a security chain.

Oh, God save me from fools. Growling, Aiden pushed the door open. The hardware anchoring the security chain tore free from the wall. Before Michaels could cry out, Aiden stepped inside and closed the door behind him. In the next heartbeat, he seized Michaels’ right wrist and squeezed until the other man screamed and dropped the pistol. It hit the hardwood floor with a clatter but didn’t discharge.

“A gun?” Aiden released the other man’s hand. “Now I ask you, what kind of a reception is that?”

Labels: beginnings, inciting incident, novel writing, plotting

This week on The Wet Noodle Posse Blog

Noodlers continue our discussion about Plotting.Monday, March 24th: Norah Wilson "Beginnings"Tuesday, March 25th: Merrillee Whren "A Pantser Dilemma--Plotting"Wednesday, March 26th: Esri Rose "Plotting with Theme"

Noodlers continue our discussion about Plotting.Monday, March 24th: Norah Wilson "Beginnings"Tuesday, March 25th: Merrillee Whren "A Pantser Dilemma--Plotting"Wednesday, March 26th: Esri Rose "Plotting with Theme"Thursday, March 27th: Guest Blogger Kendra Sawicki "Avoiding the Dreaded Info-Dump"

Friday, March 28th: Q&A (Readers ask questions. Noodlers answer.)Have a productive writing week!

Q and A Friday #2

It's Good Friday, a busy day and the start of the busy Easter weekend, so there may not be many Qs today or many As , but here we go!

Do you have any questions about this week's plotting topics?

We've talked about subplots, about making lists of events, about troubleshooting, and about making collages.

Or do you have a plotting problem you'd like to discuss?

We may not get to it all right away, but go ahead and ask!

And

Happy Easter to everyone!

Labels: plotting, Q and A

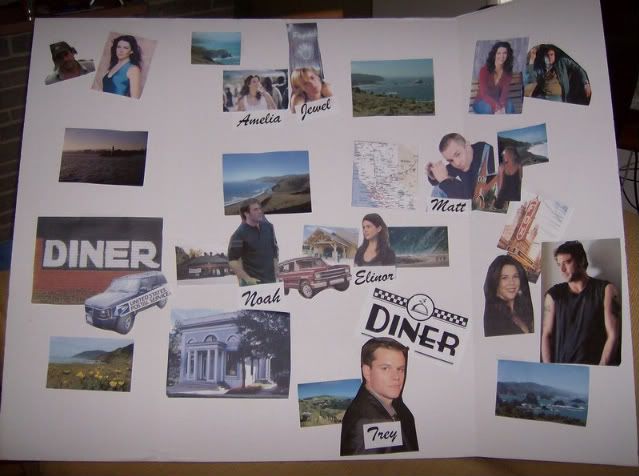

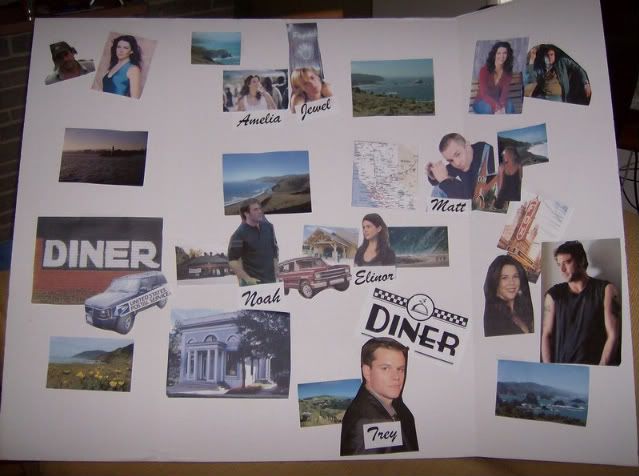

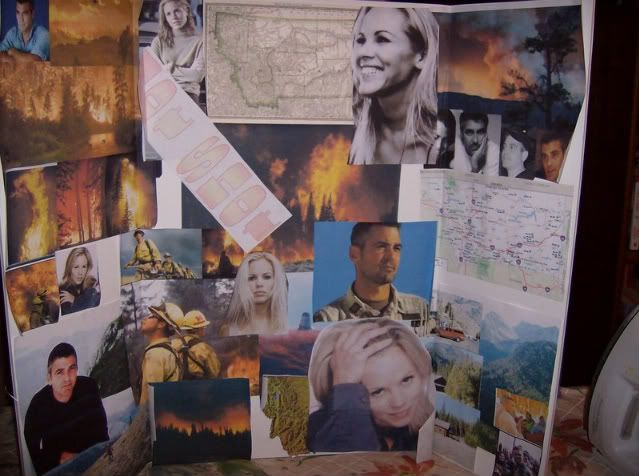

Collaging

All this plot talk has me jittery ;) I am a pantser, absolutely. I start with an idea and run with it, until I hit a wall, then I stop. I’ve tried the index cards, but once I write them, I never look at them again.

So to focus, I make a collage.

I know some people use the organic method, where they just go through a stack of magazines and rip out whatever appeals, then see how things can relate to their stories. They claim to find ideas in this manner, twists to the story that they didn’t expect, as if their muse prompted them to tear out those pictures.

I do my collage about half way into the story. By then I have a pretty good idea of who my characters are, but the story needs focus, needs connections, and where the pictures go gives it that connection, gives deeper meaning to the objects I place in the collage. It also helps me sequence the story – what should happen when, what needs to happen before something else can happen.

I always start my story with a physical picture of my hero and heroine, usually based on actors. I print out those pictures, as many as I feel I need, ones I feel fit my characters. For example, I wouldn’t get a picture of my heroine/actress in an evening gown unless that character wears an evening gown on some occasion. Gerard Butler in Tomb Raider fit my hero in Beneath the Surface, but his appearance in Reign of Fire fit my hero in Don’t Look Back.

Then I think about what’s important to the character. Does my heroine have a cherished piece of jewelry? Does my hero have something that reminds him of his family, his past? I google images and print.

I think about what kind of house they live in and search for that. I think about what they drive, where they are. If it’s a real place, I find a map so I can reference it while I’m writing. If it’s not, I find pictures of what I think the place will be like. I’ve not yet created my own maps because, well, my class could tell you I can’t draw at all.

Once I have my pictures, I buy those science fair display boards (JoAnn Fabric has them for reasonable prices.) I get my glue stick and my scissors and I cut and arrange, then glue. Then I prop my board up to look at while I’m writing.

I’ve also made some digital collages, though to be honest, I wouldn’t know how to do it on a Windows machine. I used to use AppleWorks before the dh upgraded to Leopard, and now I use Pages. Again, I find the pictures, but drag them onto the document. These actually do work well as “book covers” on my notebooks. (I buy the binders with the clear covers and insert my collage, then print out the story to put within – easier to keep track of.)

I prefer the scissors and glue collage, because you have different parts of your brain working on the story as you physically put it together.

Do you collage? How do you do it?

More articles on collages:

Jennifer CrusieVision WorkshopMy digital collage for my Wayback Rodeo story.

My digital collage for my WIP.

My physical collage for my WIP.

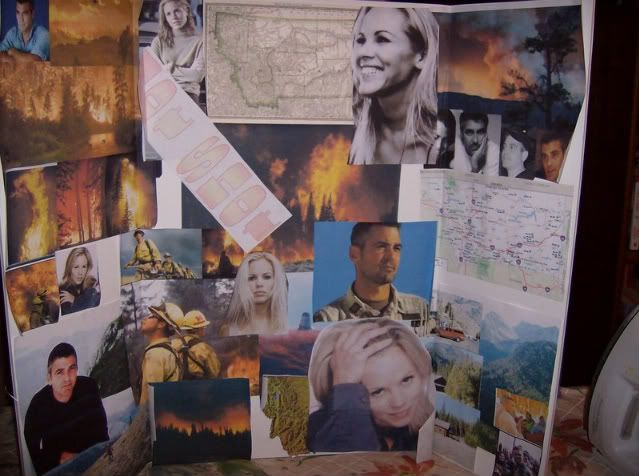

My collage for Hot Shot. I used maps and pictures of Montana and fires to help me focus.

My collage for my 2006 Nano book. I’m hoping it will help me revise. It certainly helped me change who the hero was.

Labels: character development, collage, plotting, writing

Power PlottingBy Mary Buckham and Dianna Love, co-creators of Break Into FictionTM

Creating a novel-length story requires compiling a huge amount of information from character

development to the final resolution. Every writer has his or her own way of pulling all of that together to end up with a book, but regardless if you are a pantster or a plotter there are certain elements in all commercial fiction.

There’s no way we can take you through all the levels of Character-Driven

Plotting in one blog article, so we’d like to go over some of the biggest problems or issues we see in our Plot YOUR Book in 2 Days Retreats attended by new writers and mass market published authors.

All writers get excited about a story because of something that ignites an original idea or a scene they envision or a character talking to them. That’s great. You need to hold onto what excites you about the story. New writers and published authors run into similar problems, but for different reasons. A newer writer may not be familiar with all the components of a compelling story as they are often still going through the initial learning curve. A published author is very aware of what is necessary, but does not recognize when a story is lacking those components – how to find plot holes.

Trouble shooting a novel length commercial fiction story and rejection letters:

- The infamous “sagging middle” indicates a lack of plot, lack of turning points, lack of stakes rising and possibly a lack of character development.

- A rejection that says “Interesting story concept but I didn’t connect with the characters” means character development is lacking.

- A rejection that says “…not big enough to be single title” may indicate a large enough premise for a single title, but what you consider subplot is not significant to the central story line.

How do you find these holes? A good place to start is with the character to see if he/she is truly motivated or just “doing things the author needs them to do.” Or, ask yourself if your character’s external goal is really strong, or worthy of an entire book.

Another problem we see often is that the central character(s) don’t really accomplish anything or move the story forward – they just go from one non-escalating action to another that has no true impact on the story.

Writers don’t always realize they are creating plot holes or unmotivated characters, because as writers we tend to be to close to the work. The best way to locate problems in the plot and/or with the characters is to ask a more experienced writer or find a instructional program that will show you how to recognize weaknesses. If that is not available, then here’s an exercise: Analyze each scene to make sure that whatever action is happening in your story impacts the external plot line or the internal growth. In the strongest stories, the action impacts both.

If you find yourself challenged by any of the issues we’ve brought up in this blog, speak up as we’ve been able to help lots of writers, both published and pre-published, “see” their work in a new light.

So, what stumps you when it comes to plotting?

Award-winning authors Mary Buckham and Dianna Love met while teaching online and at live workshops across the country. As relatively new authors who can appreciate the mountain of resource books needed to learn the craft, they used their analytical skills to assimilate a program where writers could immediately apply new information learned to their own stories. This program is called the Break Into FictionTM Template Teaching Series. For more information, go to

www.BreakIntoFiction.com

Mining Character Arcs for Plot

Often times our stories come to us in visual flashes. We see a character in an intriguing situation. They haunt us before we fall asleep at night or when we're barely conscious in the wee morning hours. We are storytellers. It’s not our job to ask why these random characters pop into our minds, but who they are and what the story is they have to tell. It's almost as if we are the transcribers and they call the shots. Sometimes these characters are silent types and we have to drag their stories out of them before we know in which direction to go.

So, let’s say you have dear Aunt Edith in kitchen with a casserole standing over Uncle Louie’s body--in other words you have a character with problem in an interesting situation. Poor Aunt Edith didn’t snuff Louie, but she’s going to take the wrap if you don’t figure out how to bail her out. So now what? How can we push the plot forward from the inciting incident?

Okay, let’s say Edith’s fatal flaw that got her into the mess in the first place is her desire to take care of everyone, whether they want her help or not. She has a habit of showing up unannounced at the most inopportune times, often creating havoc, and yes, even occasionally death. Somehow Edith must learn an important lesson from Louie’s ill-timed demise and her embarrassing brush with the law and redeem herself. At the end of the story, we know she becomes a welcome member of her family instead of the dreaded black plague who has folks running when her number pops up on their caller ID.

We need to develop scenes that will show Edith’s character flaw and how it works against her in the opening of the story. Then we need to make a list of scenes that show her learning from her mistakes and growing into the new and improved Aunt Edith we see at the end of the story.

Now, it’s time for some brainstorming and character digging. Divide your paper into two columns. Label one “Beginning” and one “End." List scenes that show your protagonist’s fatal flaw working against him or her under the ”Beginning” column. In the opposite column, list scenes that show your character overcoming their flaw. Think BIG here. This is the time to let your imagination run free. Put your Aunt Edith through the ringer.

When you have a good number of scenes, I would suggest you order these scenes in rising intensity. In these scenes, you may have a scene that could serve as reversal--the character thinks they have finally gotten things back on track only to find things are actually worse. Your goal is to move the character toward the climactic moment where all seems lost. The character will be forced to dig deeper into herself to find a solution to her problem. Remember, only a character in conflict will grow beyond his or her comfort zone. So pile on the conflict and make them work for their happy ending.

Crafting Subplots

Happy Saint Patrick's Day

Think about St. Patrick's story, son of a Roman father, kidnapped by Irish pirates and enslaved in Ireland. If we were writing a novel about him, might we not have a subplot, perhaps about the people with whom he'd been enslaved, and what happened to them when he returned to Ireland? But why would we do this?

In

Building Better Plots, author Robert Kernan rather thoroughly discusses the use of subplots. I’m using his ideas, but also inserting my own thoughts.

Purpose of subplots  Subplots provide diversion or relief

Subplots provide diversion or reliefIn our main plots, we try to build the tension to keep the readers turning the pages, but readers also need some breathing room, some relief from the tension we’ve created. Subplots are perfect for this. At a point of high tension, turning to the subplot not only provides that “breathing room” but still keeps the pages turning to get back to what is going to happen in the main plot

Subplots as context or background – to enlarge toneOne of the ways to bring our setting to life, our time period, the “world” we are writing about is to use the subplot to show more of the place, the culture, to reinforce the tone of the story. In the case of a Regency historical, subplots can show more of what life was like in that era. In stories like Maureen’s Mossy Creek novellas, subplots show more about life in Mossy Creek.

Subplots as backstoryThis is a special sort of subplot—flashbacks illuminating characters’ backstories, subplots about the main plot, sorta. Flashbacks and backstory can enrich the main story by illuminating your characters motivations, increasing reader sympathy, or in the case of a reunion story, showing the origins of the romance.

Subplots to tell concurrent or parallel storiesOne type of subplot I love in a romance is a secondary romance. What could be better for a romance reader than two romances in the space of one book? You can use these sorts of subplots to either strengthen the theme of the main plot, show a variation on the theme, or show a complete contrast. Sometimes fiction uses a Parallel stories structure. This is where the stories of several characters are told, one after the other or a little bit at a time. The stories are connected in some way, especially at the end.

Subplots to develop CharactersShowing your main characters in the subplot gives an opportunity to show them in a different context. You can show them reflecting on the main plot or put them in a situation that shows a different part of their personality. You can show their strengths and weaknesses. Sometimes in using subplot this way you can foreshadow something important, like that first scene in Raiders of the Lost Ark foreshadowing Indie’s fear of snakes.

Placement of subplots

The most important thing to keep in mind in choosing where and how to place your subplots is to make certain they do not detract from your main plot. Subplots can be shown in one scene (like a flashback) or several, but it is important to establish the main story first. Use logical entry points and try not to interrupt the flow of the main plot. Kernan says to wrap up the subplots before the crisis begins, but I think you can vary this a little, especially if you have woven all the threads of the plot and subplots together. The subplots should be resolved before the main plot, so as not to distract from your big ending, though.

We’ve often discussed what to do when we get stuck. One more thing to try is a subplot. If I am agonizing about what sort of scene to write next and can’t think up enough scenes to get me to the end of the book, sometimes it is because my story needs a subplot. In my latest book, The Vanishing Viscountess, that is how the secondary romance was born and I had fun thinking of ways to weave it in to the main plot.

What are some of your ideas about subplots?

Do you have examples of subplots done well? Some of your favorites?

Come to my website and enter my contest for a chance to win one a signed copy of my The Mysterious Miss M and How to Seduce a Duke from Kathryn Caskie, celebrating the release of Kathryn's How to Propose to a Prince.Labels: How to Write, Subplots

This Week on the Wet Noodle Posse Blog

Monday, March 17th: Diane Gaston "Crafting Subplots"

Tuesday, March 18th: Lorelle Marinello "List of Possible Events"

Wednesday, March 19th: Dianna Love and Mary Buckham "Plotting"

Thursday, March 20th: MJ Frederick "Collages"

Friday, March 21st: Q&A (Readers ask questions. Noodlers answer)

Labels: plotting

Question and Answer Day

This is the day we answer readers' questions about writing. Who has a question? Don't be shy!

Labels: writing questions

Guest blogger Katey Coffing on Plotting

Hello from the guest blogger! My name is Katey Coffing, Ph.D., and I was fortunate to be a 2007 Golden Heart® finalist along with several of the 2003 Noodlers. (Since the Wet Noodle Posse led the way by choosing such a memorable name, we in the '007 GH crew call ourselves "Licenced to Sell." ;-) )

I'm delighted to have a fantastic day job: I'm a certified life coach who helps writers succeed. Because of that, I've seen just about every kind of roadblock our fertile, writerly minds can throw at us. You've probably experienced a few of them yourself. Perhaps you were zooming along on a manuscript, only to be become inexplicably stuck. (Or even sideswiped by a writer's block so vicious you gave up and hid the manuscript under the floorboards.)

That block may not be the product of a fickle muse or of a recalcitrant idea generator. Your subconscious may have been trying to tell you something's amiss in the structure of that story--in the plot and how your characters react to it.

Structural flaws aren't always obvious to your conscious mind. But your subconscious realizes a great many things, many of which it has trouble communicating to its more articulate roommate.

This can result in a block of colossal proportions as your mute subconscious tries to get you to stop building on shaky ground. The translation: There's something seriously wrong here. Don't add anything until you figure out the problem. So if you're feeling stuck and you're not sure why, put on your Building Inspector's hardhat and dig in.

What kind of structural problems should you look for? Well, it's an unfair truth that there are as many ways to botch a good book as there are to write one! But here's an example from my own experience, and the solution I created.

Years ago while nearing the end of my second romance manuscript, my momentum dribbled through those aforementioned floorboards. Instead of writing the story, I found myself testing new ways to organize my drawer of binder clips and rubber bands. After a few weeks of this (it was a large drawer), I needed answers. I re-read many chapters and realized the scenes after the midpoint of the book felt unfocused, and so did my characters. Seat-of-the-pants writing had worked great for my first manuscript, but pantsing the second had become a miserable experiment. My story needed a major overhaul.

To get a feel for the necessary repairs, I consulted several of my favorite advisors: Dwight Swain's Techniques of the Selling Writer

http://www.amazon.com/Techniques-Selling-Writer-Dwight-Swain/dp/080611197/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&s=books&qid=1205391373&sr=8-1, Debra Dixon's Goal, Motivation and Conflict

http://www.gryphonbooksforwriters.com/si/1.html, and Carolyn Greene's Prescription for Plotting

http://www.theplotdoctor.netfirms.com/workbook.html.

With their help, I created a template--a master list of key ingredients for can't-put-it-down scenes. These included (among other things) a "ticking clock" to propel the pace, crafty opening and closing hooks, unique scene strategies and obstacles for each main character, plot (and character) surprises, and a meaningful symbol that would enhance the emotion for my reader. (My template included things I felt I already did well AND things that could stand improvement, so a list customized for your writing might differ from mine.)

Wow--just a simple list, but having it put me back in control. Now I had a template to help me think through each scene of my novel! And I could easily tweak which ingredients I used from one scene to the next. (By the way, pantsers who would rather chew tacks than plot can use this technique for revisions.)

I tested my solution by looking at scenes I'd already written but seemed flat. With the list in hand, I was able to brainstorm new plot twists and sharpen my characters' goals, sparking life and energy in the manuscript! And new scenes flowed easily because I knew from the very first sentence what that scene needed--and I had the road map to make it happen.

So next time you get stuck, consider whether there's a structural problem that has jammed your writer brain. If so, be willing to bring in the jackhammers, welding tools, and cement trucks. (Of course, don't forget the studly construction crew.) And whether you plot or "pants", I'm wishing you a finished novel that brings you (and your readers!) joy.

--

Goalmeister Katey Coffing, Ph.D. helps her clients complete and polish their manuscripts, create kick-ass queries and synopses, and get The Call from agents and publishers. Discover more at Women-Ink.com.

http://www.women-ink.com/Labels: Kate Coffing, plotting, Women-Ink

Keeping Organized - Writing With A Notebook

When I talk to other writers, the one thing we really seem to have in common is the sense that we just don't have enough time to write. We have jobs, families, household duties, take care of aging parents and grandparents, volunteer...you name it, we do it.

The other thing we have in common - we often put our own need to write last.

My critique partner suggested I start using a notebook. I can always find few minutes to jot down a paragraph, a few lines of dialogue or ideas for the synopsis while waiting in line for kids to get out of school, soccer practice, boring PTA meeting etc.

And it really worked! A page in the notebook here, another there, voila! It might not sound like a lot, but when you're not getting anything written, and all of a sudden are getting a page a day written - that's a book in less than a year!

There's an added bonus. When I transcribe from the notebook to my word processing program - I'm already doing some revising and editing, making my rough draft not so rough. Not only am I doing the little things like adding more flavor to the prose already written, I'm also adding additional paragraphs. I end up having much more when I'm done than just what was written in my notebook.

My notebook writing often works best when I'm at the beginning of the book, when the ideas are more fresh, and I'm in that rush to get everything down on paper. It's also a lot easier for me to use my notebook when I'm in the proposal stage of writing, when I'm really formulating ideas (I'll have several going on at once).

The middle - not as easy to write in the notebook. Often, that's when I'll tuck in some research materials into my notebook.

In fact, I now have a car bag for my writing. It contains a pen, my notebook and research materials I haven't had time to read, but are important to the book I'm writing. Here's a sideways picture of my car bag hanging on the doorknob to remind me to get it. (Why it's sideways, I'll never know. If I were a children's writer, I'd say I lived in a sideways house.)

When I'm at the end of a book, the notebook writing is easier once more. The end is in sight, I see the scenes clearly in my head, and I'm back to that rush of getting everything on the page.

Little Hints:

- Decorate or get an unusual notebook. This will make it easily findable in the house, car, kid's backpack, whatever. And yes, I've run around like an idiot trying to locate my notebook.

- I'll often work on a few ideas at the same time. Use a new page for different ideas, and always write the Manuscript name at the top of the page.

- After you've transcribed from your notebook into your word processing program - draw a line though the text, so you don't keep running across it and not remembering what you've done and not done.

When I'm stuck in my writing, but I have notebook time, I try to think of this as an opportunity, rather than staring into space. I can use that time brainstorming. Play the whatif game with my characters. I've read that we're more creative when we're writing longhand than solely at the computer (which up until a few years ago was the only way I wrote) so use this time to whip out something unexpected.

I'm interested if you use a notebook or not, and if yes - how do you use it?

Labels: Jill Monroe, writing

Outlines or Index Cards?

Okay, I admit it. I’m not cool and hip and an unplotter. I’m a methodical outliner. I have even dabbled with index cards but found them to be a little too free-wheeling for me. They just didn’t give me the high of an organized linear document. I like structure. And, yes, I do write my short stories and novels in a linear progression from Chapter One, Scene One to “The End.” Writing something out of order, sacrilege, I think. I wouldn’t say it--really. What I’ve discovered is that what works for some doesn’t work for all. And, like Terry mentioned yesterday, the key to finishing your novel is to find what works best for you.

Okay, I admit it. I’m not cool and hip and an unplotter. I’m a methodical outliner. I have even dabbled with index cards but found them to be a little too free-wheeling for me. They just didn’t give me the high of an organized linear document. I like structure. And, yes, I do write my short stories and novels in a linear progression from Chapter One, Scene One to “The End.” Writing something out of order, sacrilege, I think. I wouldn’t say it--really. What I’ve discovered is that what works for some doesn’t work for all. And, like Terry mentioned yesterday, the key to finishing your novel is to find what works best for you.

You might be an outliner if…

1. You own a Dymo Labeler and you use it on a regular basis.

2. Your gift wrap ribbons are organized by color in one of those plastic shoe rack things that hangs on the inside of a closet door. If people, meaning your husband or child, puts the ribbon back in the wrong pouch, it bothers you. A lot. But I digress.

3. You actually liked writing term papers in high school and/or college

4. You come to a full stop at stop signs in your neighborhood, even when there are no other cars around.

5. You write your daughter’s name on the sole of her pointeshoes and add a symbol to encourage a rotation system of ■, ●, ▲, ●● in permanent marker.

With my first novel, a historical romance, I didn’t outline. I pantsed my whole way through and when at long last I typed “The End,” about 650 pages later, I discovered I’d written at least two books with multiple subplots. With subsequent novels and my published short stories, I found outlining kept me on track. Over the years, I’ve added more and more detail in my outlines to highlight my strengths and to overcome my weaknesses (readers’ emotional connection to characters). I start with characters’ backstory. Then I move on to the story itself. In addition to the actions of the characters, with each scene, I also list descriptions of the setting, sensory details that I might want to use, and the emotions for each character in the scene. I also check to make sure I’ve included a sequel (reaction) built into the plot after each scene. If dialogue comes to me, I throw it in, too.

Here’s an example of what an early version character backstory for Widow’s Kiss looked like:

Christian Redding: Runs father Archibald Redding’s plantation in the West Florida parish of St. Tammany (Louisiana). Father was a former British soldier who fought in the Revolutionary War. Christian’s hard work and love for this property has made the timber plantation successful. He wants stability, but change is in the wind. In the past year, his widowed father has begun to spend their profits frivolously and, worse yet, he’s decided to marry a notorious young widow rumored to have had a hand in her previous husbands’ deaths. If that weren’t enough to disturb his peaceful routine, his prodigal brother, recently returned from the Orient, is trying to convince their father to join with other plantation owners who are planning an insurrection against the Spanish. The family could lose everything. Physical attributes: Tall, broad-shouldered, golden-haired, blue eyes, chiseled face. Rarely smiles. Tiny lines around his eyes from being in the sun and squinting. Browned a bit from the sun from overseeing the felling of timber. Looks like a taller, younger copy of his father. Goal: To protect his father from getting hurt by this woman he plans to marry (even if it means preventing the marriage) and to keep the Redding plantation out of the insurrection.

I then type similar paragraphs about all the main players in the story: the heroine, the hero’s father and brother, the red herring characters if there’s a murder involved (which in this story there is), the real villain, etc.

This is what I did for a typical scene in the same story:

Chapter One

Scene 3:

Setting: August. Warm morning. New Orleans. Windy from river. Whale oil lamp posts. Vieux Carre. Wrought iron balconies with plants, plastered brick edifices with some crumbling brick showing through. Lush courtyards and patios. Shutters battened down facing the road. Sounds, drip of water, footsteps on banquettes (boards), hush of Sunday morning. No bustle yet. By afternoon the bustle would return. Creoles enjoyed their Sabbath. Passes the Planter’s Bank at Chartres and Bienville. Rue Royale. Courtyard patio. Enters with wagons through wide gate which faces the street, porte cochere. Passes through high-domed passage way into court with bricked patio. Center fountain. Side kitchen and slave quarters detached from main dwelling. To the rear, a slant of sunlight illuminates the interior of an empty carriage house, with empty horse stalls. Window openings wide with arch at top and fan transoms. Wide window sills holding flower pots and what looked like rosemary. Flat green roof tiles, wet with dew, green was striking rather than half-round red tiles. Moresque style wrought iron railings on the second floor galleries with a D in the center. First husband’s monogram. Glimpse of brocade upholstery in parlor when wind shifts a lace curtain. Emotion: Angry that his father is marrying, that his brother is encouraging father to side with nationalists, and that his father sent him to escort the widow to the plantation. Action: Christian sees heroine Desiree for the first time. She’s as beautiful as she’s rumored to be. He learns that her cousin is also coming to the plantation with them (something he’s pretty sure his father doesn’t want) and that the widow isn’t bringing any of her expensive furniture (which he knows his father did want), which she’s sold along with her home to improve her finances. What happens merely confirms his suspicions that this marriage between Desiree and his father is ill-fated. She’s surprised that her fiancé sent his son and that his son looks so much like his father. Once she convinces Christian that her cousin must come with her, she seems particularly concerned by the time. He realizes why as the wagons make their way through the city and the people leaving church treat Desiree with disdain. He feels sympathy for her, which he doesn’t want to feel. Hook: A man in the road at the edge of town calls out to Christian, warning him that no one survives the widow’s kiss.

I may not use all the details I list in the setting, and I may add more when I actually write the chapter. For example, I added in sunlight hitting the wet tile roof and blinding the hero when he initially meets the heroine, so that he can hear her voice but not see her face until she moves out of his blind spot. I also added sounds and smells. I add dialogue when I do the real scene. But what I’ve written in outline gives me a good starting point. If I’m smart, I’ll go back and add in all the characters’ scene goals if I haven’t included them the first go round of outlining.

One of my writing friends swears by index cards. I think they’re for people who need some structure to get started but don’t want the detailed formality of a thirty-five page, single-spaced outline. Yes, mine are that long. This friend, though, writes important plot points, scenes, sequels, turning points, the black moment, resolution, etc. onto separate index cards. Then she organizes them. She puts the character GMC’s on index cards, too. At times, she even uses colored index cards to delineate hero and heroine plotlines so that when she spreads them on the floor, she can see where her hero and heroine’s journeys might need a little more attention.

You might be an index card plotter if:

1. You like to spread things out on the floor

2. You like shuffling cards

3. Outlines give you hives* (this could also make you an unplotter)

For me, outlining is a comfortable method of organization; it’s familiar, and I like that it’s linear. It’s essentially my safety net. I do diverge from the outline if something I’ve planned isn’t working or if I get a brilliant idea that makes the story work better. Sometimes, once the first draft is done, I throw away completely written scenes (I save them in a file for future use—just in case), I might add some new ones, and I might move some around to better suit my plot. The biggest benefit to me of outlining is that I can see without writing a full chapter what I need to cut or add to, whether I have enough conflict, whether my plot is moving, etc. In the long run, it saves me time revising.

How about those of you who outline? What makes this method comfortable for you? What tips for outlining do you have to share? Anecdotes?

Labels: outlines for novels

The Organic Approach (Or I Have No Idea What I'm Doing)

One night about a dozen years ago, I sat at my computer to perform an experiment: to see if I could write something. I had a scene in mind, a fictionalized version of a real-life incident in Paris. That scene–the first piece of fiction I ever wrote–wound up in Chapter Four of my first manuscript. And it survived intact to appear in Chapter Ten of my recent release,

A Perfect Stranger.

So began my haphazard, horrifying writing process. I still write scenes as they come to me, in a completely random fashion. I skip bits I think I'll need but don't want to deal with at the moment–if I'm lucky, I'll discover I don't need them at all. I don't keep track of where my characters have been, and I have no idea where they're headed. I'm spoiled, I'm undisciplined, I'm a mess. But I've stopped stressing over my shortcomings because my crazy method appears to be working.

There was a time I thought there was something wrong with my routine, and I attended every plotting workshop I could find. I took copious notes on charts, grids, notebooks, outlines, arcs, lines, color-coded columns, act-based organizational plans–you name it, I considered it. And then I tossed it all aside with a shrug. I figured I could spend lots of time organizing my thoughts, or I could let them spill onto the manuscript pages and see what developed. Chaos suits me, and I'm sticking with it.

When people ask me about my process, I usually answer, "You don't want to know." One night, a friend pressed for a response, so I told her. In detail. She actually turned a slight shade of green. "You're right," she told me when I finished explaining. "I don't want to know."

You don't want to know, either. Which will shorten this blog post considerably.

I do need a couple of things before I open a document and type Chapter Whatever: a character, a mood, an incident. Some sort of story premise is nice, but not necessary. I began

Learning Curve with nothing more than the image of a slightly depressed man walking down a wide, deserted corridor.

Make-Believe Cowboy got its start when I envisioned a scene where a horse-savvy movie star scared a rancher who thought he'd break his neck riding bareback. That's all I had when I started writing those two books. No names, no goals, no motivations, no conflicts, no ends in sight.

I'm the Unplotter.

Okay, so I need more than an image or an idea if I want to sell on proposal (and I do). I need to come up with a couple of things that might happen, invent some fuzzy character backstories, and weave them into a vague-but-compelling synopsis. I also need an editor who'll trust me to pull another rabbit out of my plotless hat.

I realize now why I started writing when I discovered romance novels: I'm a completely character-driven writer. So it makes sense that I'd feel at home in such a character-driven genre. And since this is genre fiction, we all know how the story's going to end, right? What makes the reading fun is finding out how

this couple will arrive at their happy ending. And what makes the writing fun for me is tagging along on their journey.

Plots? Who needs 'em? Once I figure out what makes my characters tick, I stop worrying about what happens next. I stumble along with my characters as we make our way to The End, with fits & starts, with a little second-guessing and a few retakes, with no idea what's going to happen next. Just as I do with my friends in real life.

Are you an Unplotter? Are you willing to jump off a story cliff, figuring you'll write in a parachute at some point on the way down? Are you ready to toss aside your charts and graphs and embrace the unknown? Or does the anarchy on your pages make you feel insecure when your critique partners mention structure?

Terry McLaughlin is busy unplotting the next two books in her new Built To Last

series for Harlequin Superromance. Look for the first book in the series, A Small-Town Temptation

, in May.

Noodler March Releases

Delle Jacobs

Delle Jacobs Aphrodite's Brew

Samhain Publishing

MJ Frederick

Where There's Smoke

Samhain Publishing

Janice Lynn

The Heart Surgeon's Secret Son

Harlequin Mills & Boon Medical

Labels: Delle Jacobs, Janice Lynn, MJ Frederick

This Week on the Wet Noodle Posse Blog

We continue this week with our focus on Plotting. Please join us.

Monday, March 10th: Terry McLaughlin "The Organic Approach (Or I Have No Idea What I'm Doing)"

Tuesday, March 11th: Maureen Hardegree "Outlines or Index Cards?"

Wednesday, March 12th: Jill Monroe "Get a Notebook and Get Organized"

Thursday, March 13th: Guest Blogger Kate Coffey

Friday, March 14th: Q&A (Readers Ask Questions, Noodlers Answer)

Labels: organization, plotting, writing

We brought the following supplies to help us plot:

We brought the following supplies to help us plot: